For more than two months now, a ruptured storage well has poured thousands of tons of gas into the Porter Ranch section of Los Angeles. The Aliso Canyon leak is huge—California’s largest known source of methane emissions at this point—but not compared to another font of wasted gas miles away in Venezuela.

Punta de Mata is home to the world’s largest gas flare, one of the flaming chimneys used to burn off excess natural gas at oil wells and other energy sites. In 2012, it incinerated about 768,000 metric tons of natural gas, almost 10 times the amount given off so far from the Southern California Gas Company’s facility at Aliso Canyon.

Methane, the primary component of natural gas, is 84 times more potent as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide over two decades. As countries seek to comply with the new UN climate accord by slashing emissions, both gas flaring and leaks remain persistent problems. Though widespread, they can be difficult to track, given that methane gas is invisible and odorless.

Now, high-tech cameras and satellites are capturing those releases better than ever, putting pressure on companies and officials to take action. Flaring gas has a much lower impact on the climate than a vent directly into the atmosphere—the flame converts gas into an amount of carbon dioxide that will have 30 times less warming potential in the near term. Still, the methane hotspots spanning the globe add a hefty sum to its greenhouse gas pollution.

Night Beacons of Gas Waste

The Punta de Mata flare was measured in a new study that offers the most comprehensive look so far at gas being burned off around the world. The paper, written by researchers at NOAA and co-funded by the World Bank, attracted little notice when it was released on Christmas. But it’s the first set of results in a four-year effort to use new infrared imaging technology to map out where, and how much, natural gas is being flared. (See related story, “Space View of Natural Gas Flaring Darkened by Budget Woes.”)

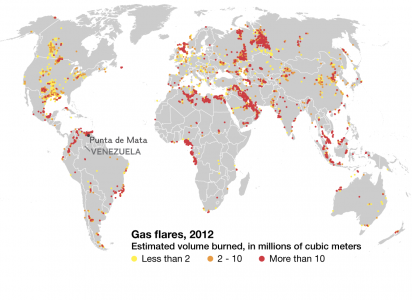

The researchers estimate that 143 billion cubic meters of gas was flared worldwide in 2012, equivalent to 3.5 percent of all that was produced. “Because flaring is a waste disposal process,” the paper notes, “there is no systematic reporting of the flaring locations and flared gas volumes.”

With a new satellite tool called VIIRS, or Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite, researchers found more than 7,000 flare sites. Russia flared the largest volume of gas (25 billion cubic meters, about half what the state of Colorado produces in a year), according to the study, while the United States had the highest number (2,399) of flares.

VIIRS is designed to operate during the daytime, monitoring land and water cover. At night, its “operators would tell you, well, there's nothing to see," says Christopher Elvidge, a NOAA scientist and the paper’s lead author. But the researchers “lucked out,” he says, when an engineer thought to use the equipment at night, when it could isolate flaring activity.

As a result, researchers were able to assemble the most complete view yet of the world’s gas waste, one that departs from previous assessments. In the latest VIIRS-driven ranking, Iraq flared the second largest volume of gas, followed by Iran and Nigeria.

It was “a little bit surprising,” Elvidge says, “that Iran and Iraq have as much gas flaring as they have. We were expecting Nigeria might be second or third.”

Flaring often occurs because oil producers don’t have the pipelines or the market for the gas that sometimes comes up along with oil; it can also happen for safety, to avoid an explosive buildup of methane during emergencies or maintenance, for example. Last year, the World Bank launched an initiative aimed at ending all routine flaring by 2030. So far, several energy companies and governments have signed on.

Having a way to monitor flaring will be key to the effort. Elvidge’s research team plans to keep fine-tuning its methods, releasing results sometime this spring for subsequent years to see how they compare with the 2012 data.

"We're going to be able to track these mega-flares through time," he says.

Focus on Mega-Sources

The new paper notes that 90 percent of the gas flared is coming from just 30 percent of the sites. Likewise, when it comes to leaks from U.S. sites, “a small number of facilities are responsible for a large percentage of the emissions,” says Mark Brownstein, vice president of the climate and energy program at the Environmental Defense Fund, which supports stronger methane regulations.

The Environmental Protection Agency has proposed rules aimed at reducing leaks, but they would only cover new wells and facilities, not existing ones. Some companies are already taking steps to find and fix problems, participating in a voluntary EPA program. But as ongoing leaks in L.A. and elsewhere show, many sites are still vulnerable. Aliso Canyon is among than 300 similar storage sites across the country, and it’s one of the largest.

Two key factors helped highlight the Aliso Canyon leak: One, the gas was stored at the end of the supply chain and contained mercaptans, the odorous additives used to make leak detection easier in homes. Two, EDF and the environmental group Earthworks released infrared footage of the leak that got more than 1 million views on YouTube. (See the video above.)

The footage was made possible with special cameras developed over the past decade that can transform transparent plumes of gas into vivid, dark clouds. Alan Septoff, strategic communications director for Earthworks, says the group was able to acquire its $100,000 camera because of “one very interested and supportive donor.”

Septoff says its camera is now traveling all over the country. “Everywhere we go, we find air pollution from oil and gas development,” he says. “When invisible pollution becomes visible, regulators and decision makers start paying attention to community complaints.”

High-tech eyes on the sky ultimately could help snuff out all those invisible methane clouds and hard-to-detect flares, which threaten to undermine countries’ Paris commitments. In the U.S., so dependent on natural gas as a means of weaning itself off coal, the issue goes far beyond the immediate crisis in Los Angeles.

Both in the United States and globally, Brownstein says, “California is just a little microcosm of the kind of challenge, but also the opportunity, that exists.”

By Christina Nunez National Geographic PUBLISHED JANUARY 13, 2016

The story is part of a special series that explores energy issues. For more, visit The Great Energy Challenge.

On Twitter: Follow Christina Nunez and get more environment and energy coverage at NatGeoEnergy.