Washington state environmentalists are cheering the demise of a greenenergy project, saying it’s good news for Vancouver Island’s orcas. Say what? Yes, it’s true. And no, not everyone was thrilled when the Orca Conservancy took on this fight.

At issue was a plan to place turbines on the ocean floor off Whidbey Island. The tidal-energy proposal seemed, by definition, to be everything any environmentalist would embrace — so when the Orca Conservancy fought the idea, some reacted as though they had just found Tina Fey sticking a knife in Amy Poehler’s ribs.

“We took a lot of flak,” the conservancy’s Shari Tarantino said Friday, on the phone from Seattle.

But the truth, she said, is that the scheme was a threat to the iconic, endangered resident orcas that range from southern Vancouver Island to Puget Sound.

The plan’s proponents, not surprisingly, disagree — though it’s all moot now with news that they have officially abandoned the idea.

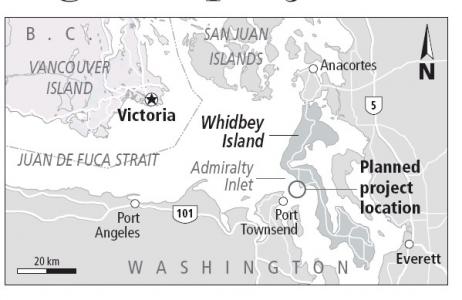

The story goes back to 2007, when the Snohomish County Public Utility District applied to place two, four-storey-tall turbines on the seabed west of Whidbey Island (best known to Victorians as the base of the U.S. Navy jets blamed for the sonic Rumbles that periodically shake our homes). Tidal currents would turn the turbines, generating local, clean energy in a pilot project whose lessons could be applied elsewhere in Puget Sound.

The Orca Conservancy didn’t even know about the idea until alerted by Vancouver Island whale researcher Paul Spong. The group was immediately concerned, though. The turbines would have been at the entrance to Admiralty Inlet, on the route the orcas take when moving from their main feeding ground — the area from Haro Strait to the outlet of the Fraser River — to southern Puget Sound when the chum salmon run each fall. The fear was that noise from the turbines would have deterred them from doing so. Also, the idea of whales — or a dozen other protected species — swimming into the turbine blades was ghastly.

The public utility had a different take. The top of the turbines would have been 45 metres below the surface, deeper than orcas typically dive, says spokesman Neil Neroutsos. The two sides differ on the noise question, too. “We studied the issue thoroughly,” he said. “All of our research indicated there would be minimal impact on orcas.”

In any case, in May 2013 the Orca Conservancy led a coalition of environmental, aboriginal and whale-tourism groups that rose up against the project, slowing its progress. “It added to the complexity of the project and added to the overall cost,” Neroutsos said.

In late 2014, after $8 million had been poured into pre-construction work, the utility shelved the idea. It kept the necessary permits, though, just in case a deep-pocketed partner showed up to help continue the initiative. But when that didn’t happen by the end of 2015, it let the licences lapse. The turbines were sunk (figuratively, not literally).

Neroutsos said the utility hopes the lessons from the Whidbey Island plan can be applied to tidal-energy projects elsewhere. That actually matches what the Orca Conservancy is saying — sort of.

“Green energy projects often go unchallenged by environmentalists, especially ones under water, so when we first raised concerns about this one, we were sort of going against the current,” Tarantino said in a statement.

“That said, our group is fully supportive of finding alternatives to fossil fuel. We are not opposed to tidal energy in the right location, but clearly this was not it.”

Times Colonist 9 Jan 2016 JACK KNOX